Eriksson Striking Distance Equation

The earlier equation, which relates striking distance to return stroke current, does not imply everything. Because the earlier lightning models assumed that the striking distance depends only on the return stroke current. However, Eriksson found this was not a fully correct prediction. He showed that the height of the structure also matters. A taller structure creates a stronger electric field at its top. Obviously, a stronger field attracts lightning earlier. So, Eriksson introduced height height-dependent striking distance formula. He introduces two different formulas. This is because lightning behaves differently for shield masts (vertical spike or lightning masts) and shield wires (horizontal conductors).

(A) Equation for Shield Masts\[S = 0.84 I^{0.74} H^{0.6}\]

(B) Equation for Shield Wires\[S = 0.67 I^{0.74} H^{0.6}\]

So we can conclude as the lightning strikes an object if it comes within distance S, and this distance depends on how strong the lightning is and how tall the object is.

First Negative Return Stroke Current Magnitude

When we design lightning shielding for substations and transmission lines, we must know how strong lightning currents usually are and how often very large currents occur. This is important because the striking distance (S) depends on the lightning current (I). If we know the lightning current, we can reasonably estimate how far lightning can strike.

Most lightning strikes are negative. The first stroke in a flash is usually the strongest one. That is why we always focus on the first negative return stroke.

Measurements show that the average value of the first negative return stroke current is about 31 kA. This is for the strokes to overhead ground wires, conductors, structures, and masts. The same current becomes around 24 kA when it strikes the flat ground.

Probability Equation (Using 24 kA)

Lightning is random, hence we cannot predict it exactly. So, we do risk-based design and accept a small probability of failure. The striking distance depends on the lightning current, and the lightning current varies randomly. The probability equations tell us how often large currents occur. From the equation, we can show that, at low current, the probability is very high, and as the current increases probability drops rapidly. At very high currents, the probability of stroke is very low.

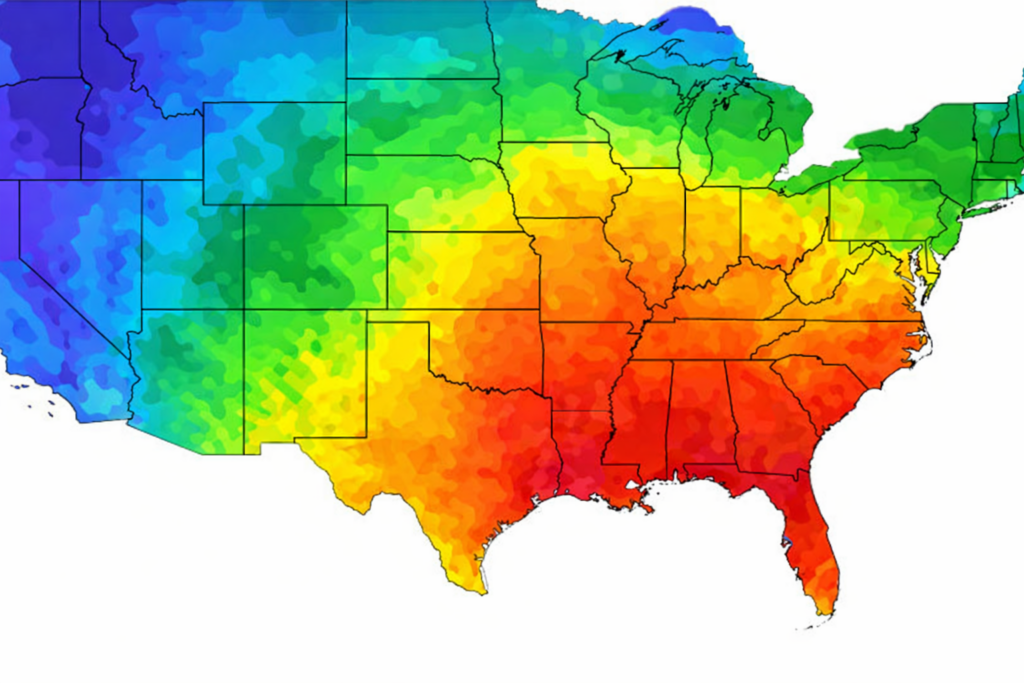

Keraunic Level

Keraunic level tells us how often thunderstorms occur at a particular place in one year. Kraunic level is based on Thunderstorm Days. A thunderstorm day means that in a 24-hour day, thunder is heard at least once. Even if thunder is heard many times in a day, it is still counted as only one thunderstorm day. So the daily method is not very accurate. This limitation may be overcome using the Keraunic level on an hourly basis.

A thunderstorm hour means thunder is heard at least once in an hour. Hence, it is more useful for engineering studies. A higher Keraunic level means a higher lightning risk. Hourly Keraunic Level maps help us quickly know the lightning activity of a region.

Ground Flash Density (GFD)

Ground Flash Density (GFD) tells us how many lightning strokes hit the ground in a given area during one year. Obviously, the ground flash density is roughly proportional to the Keraunic level. It is found that for every thunderstorm day, there are roughly 0.1 to 0.19 lightning flashes per square km per year. From GFD, we can calculate the expected number of lightning strikes to the substation area or the transmission line length.

100% Protection against Lightning is not Possible

There is no known way to give 100% protection against lightning. Because lightning is random and unpredictable. Even the best-designed system may fail. Because of this, we use simple thumb rules, especially for lower-voltage substations. Here, we standardize mast heights, fixed shield wire spacing, and experience-based layouts. These approaches are enough because an LV substation has less costly equipment. Hence, we can tolerate some risk.

But for Extra-High Voltage (EHV) substations equipment is very expensive. Here, failures can cause long outages, large financial losses, and system instability. So, for EHV substations, we need a more detailed and scientific analysis avoid overdesign and underdesign.